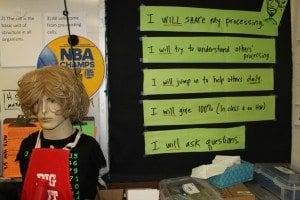

Robert MacCarthy’s classroom at Willard is packed with personality. Mannequins display messy wigs, student work tiles the walls, a disco ball dances from the ceiling. The place is high energy, high humor, and high inspiration. Stepping into his classroom, one instantly feels motivated to learn more.

Robert MacCarthy’s classroom at Willard is packed with personality. Mannequins display messy wigs, student work tiles the walls, a disco ball dances from the ceiling. The place is high energy, high humor, and high inspiration. Stepping into his classroom, one instantly feels motivated to learn more.

This semester Mr. MacCarthy (aka Mr. Mac) is implementing the Diversity of Life FOSS Kit into his science curriculum. The kit is part of a Strategic Impact Grant given to Willard Science department chair Debbie Lenz to be used by all 6th grade science teachers at Willard. FOSS (which stands for Full Option Science System) “is a research-based science curriculum for grades K-8 developed at the Lawrence Hall of Science, University of Berkeley at California. Students construct an understanding of science concepts  through their own investigations and analyses, using laboratory equipment, student readings, and interactive technology.”

through their own investigations and analyses, using laboratory equipment, student readings, and interactive technology.”

The Diversity of Life kit, specifically, explores what it means to be alive. Cells, cell reproduction, survival of organisms, and genetics are explored and analyzed, fulfilling Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). And the kit uses a variety of teaching methods: individual work, collaborative group work, discussion, readings, written assignments, and experiments.

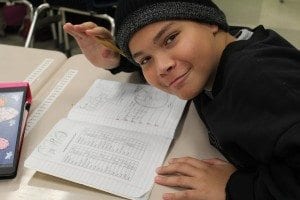

During my visit to Mr. Mac’s classroom, students participated in an observation assignment. They pulled out their science notebooks as Mr. Mac projected an image of a petri dish filled with water. “Draw a petri dish in your notebook. Make it about the size of a baseball,” Mr. Mac instructed.

During my visit to Mr. Mac’s classroom, students participated in an observation assignment. They pulled out their science notebooks as Mr. Mac projected an image of a petri dish filled with water. “Draw a petri dish in your notebook. Make it about the size of a baseball,” Mr. Mac instructed.

The exercise went like this: Mr. Mac placed small pieces of camphor in the petri dish and students were asked to observe what happened. They should draw, write, and speak their observations. The underlying question: is camphor living? And what criteria can they use as evidence to support their argument either way? Special attention was paid to their Hot Science Words: living, nonliving, evidence, habitat, cell, and organism.

As the camphor bits merged and swirled in the dish, students shouted out their impressions: “It’s clumping! It’s becoming an animal! It looks like a fish! A dolphin! A cow! It’s slowing down!” Their notebooks displayed little blobs in illustrated petri dishes. As they took notes, Mr. Mac reminded students that this is where language arts skills come in; the better their vocabulary, the better their observations.

As the camphor bits merged and swirled in the dish, students shouted out their impressions: “It’s clumping! It’s becoming an animal! It looks like a fish! A dolphin! A cow! It’s slowing down!” Their notebooks displayed little blobs in illustrated petri dishes. As they took notes, Mr. Mac reminded students that this is where language arts skills come in; the better their vocabulary, the better their observations.

After a couple minutes of inspection, Mr. Mac polled the class. “Who thinks this organism is alive? And why do you think that?” Students submitted that the camphor was moving, it was reacting, and it seemed to be growing. Therefore, it must be alive.

“Who thinks this is not alive? And why?” This was trickier, and a few students suggested they could know for sure if they were able to see the camphor under a microscope. They would look for cells or see if it dies.

“Who thinks this is not alive? And why?” This was trickier, and a few students suggested they could know for sure if they were able to see the camphor under a microscope. They would look for cells or see if it dies.

Ultimately, Mr. Mac explained that camphor are nonliving crystals. The clumping and movement were due to reactions but not indications that it’s alive.

The class seemed relieved to know the answer, even if they were wrong in their initial assumptions. Being wrong is part of the process, a part of learning. And amidst the posters and disco balls, that’s why they’re here.